Part 1 of this series examines several inconsistencies and factual inaccuracies in articles published by Pakistani leftists through the ostensibly left-wing platform Jamhoor. It focuses largely on Haqooq-e-Khalq Party (HKP) General Secretary Ammar Ali Jan’s recent response to criticisms of his party’s position on the Indo-Pak May 2025 Conflict—highlighting the historical distortions that underpin key parts of his argument (many of which apply to those he is responding to). Part 2 will shift focus toward the theoretical foundations of his claims, as well as those of other contemporary leftists, evaluating them from a Marxist-Leninist standpoint.

Analysis of HKP’s Response to Awami Workers Party’s (AWP) Critique

In this section, Ammar is largely on point in his rebuttal to AWP’s self-contradictory criticisms of HKP’s position during the Indo-Pak conflict. My only real point of contention concerns his reference to the Pakistani state’s “suicidal policies” in Afghanistan. And this leads to what is the central concern of this article: not necessarily a theoretical critique of arguments made by one Pakistani leftist or another, but the persistent inaccuracies that run through their historical knowledge (or lack thereof)—shortcomings that, even when well-intentioned, give rise to a worldview that is vague, inconclusive, and often self-defeating.

It can be assumed that Ammar is referring to the Pakistani state’s support for elements of the Afghan Taliban during the NATO occupation of Afghanistan, as well as what he believes—incorrectly—as the state’s policy of “creating” the Taliban.

If anyone can be said to have played a foundational role in the group’s emergence, it would be Ammar’s cherished “democratic” feudal princess, Benazir Bhutto.

At this point, the average Pakistani leftist would be quick to interject “even if she was in office, the military was really in charge”. But this, too, reflects a simplistic reading typical of the Pakistani left. While it is undeniable that the military remains the country’s ultimate power broker, periods of feudal parliamentary (“civilian”) rule—however flawed—are marked by a constant power struggle between feudal and military elites (their consistent common denominator being indifference to and perpetual neglect of the working class).

Analysis of HKP’s Response to Pakistan Mazdoor Kissan Party’s (PMKP) Critique

In his response to PMKP, Ammar opens by expressing disappointment at what he views as the “hostile” rhetoric typical of the “sectarianism” that has “debilitated” the Pakistani left.

While it is difficult to pinpoint exactly where Ammar situates himself on the left-wing spectrum, let us assume he identifies as a Marxist-Leninist. If so, his alarm over perceived hostility from fellow leftists is puzzling, as sharp polemics and critique were defining features of Bolshevik publications.

Ammar defends the Pakistani left’s support in the 1980s for the Movement for the Restoration of [feudal] “Democracy” after the military dictatorship of Zia-ul-Haq, describing it as a “popular front.” But what is a popular front? Traditionally, it refers to a coalition of left-wing elements—generally working- and middle-class—united against a common enemy, typically (not always) fascism—a term the Pakistani left routinely conflates with authoritarianism.

And what was the MRD? The coalition consisted primarily of the Awami National Party (ANP), the Communist Party of Pakistan (CPP), Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam (F) (JUI-F), Awami Tehreek (now QAT), and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP). Notably, the ANP and PPP were—and remain—dominated by feudal and tribal elites. JUI-F, by contrast, is a hardline right-wing Islamist party with historical ties to the Taliban, then aligned with the ostensibly secular Benazir Bhutto. The coalition also included the Pakistan Democratic Party (PDP), yet another organization led by feudal-aristocratic elites.

Whatever genuinely left-wing, working-class, or middle-class elements (i.e., elements of the Mazdoor Kissan Party) existed within the MRD made the active decision to rally around the PPP, despite Zulfikar Ali Bhutto having long alienated or purged his party’s truly socialist members. If one is to call such a coalition and its “gains” democratic, then one is hardly a Marxist-Leninist—for feudal politicians are, by definition, an anti-people and anti-democracy force. Of course, it is hardly surprising that the Pakistani left often displays a distaste for anti-feudal rhetoric—its history of aligning with (I.e., through the National Awami Party) and glorifying feudal nationalists is well documented.

None of the above contradictions were addressed in Ammar’s defense of the perplexing decision many “leftists” in Pakistan made to rally behind a feudal dynastic U.S.-backed leader—whose return to Pakistan and rise to power was unfeasible without active, consistent, and persistent imperialist support. Ammar’s defense of the MRD rests solely on the perception of democracy—not on whether said democracy is in practice, democratic or aligned with left-wing policies.

Further, Ammar refers to Zia-ul-Haq as a “U.S.-backed” and “counterrevolutionary” (what revolution?) dictator. Yet, it was not the supposedly revolutionary Zulfikar Ali Bhutto who withdrew Pakistan from CENTO—it was Zia. It was also Zia who attended the Non-Aligned Summit in Havana.

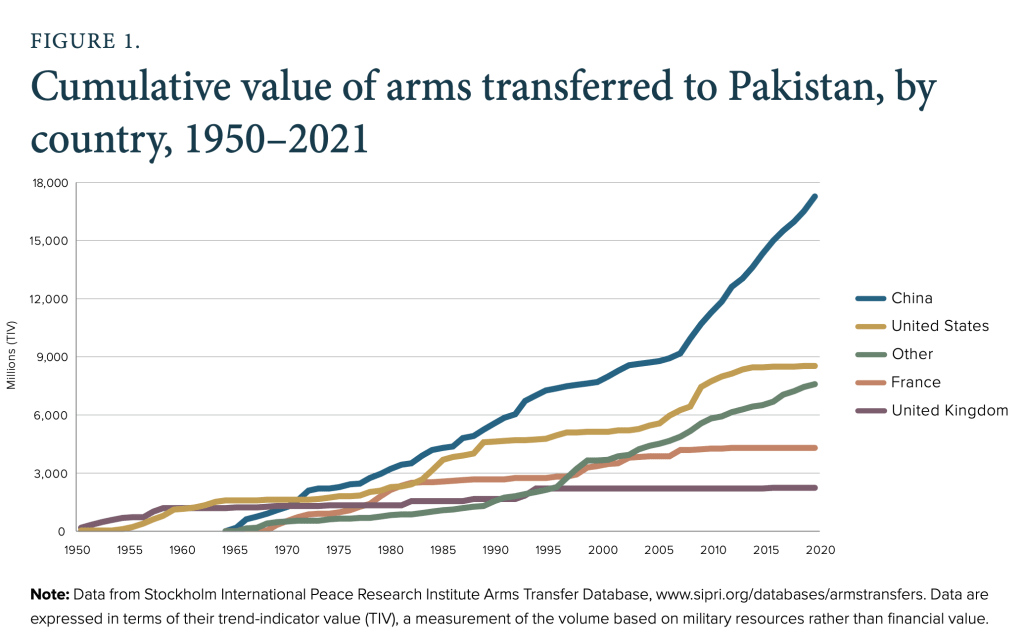

This marked our first participation in the event—and followed Zia’s application requesting Pakistan’s admission into the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). And lest we forget—though the Pakistani left often does—that then, as now—it was communist China that remained Pakistan’s most consistent and reliable ally.

Under Ayub Khan, communist China became a major arms supplier to Pakistan, beginning with the first Sino-Pakistani arms deal in 1965. Under Zia-ul-Haq’s “U.S.-backed dictatorship,” as Ammar describes it, this relationship deepened further, evolving into a full-fledged strategic partnership.

This does not mean that Zia or Ayub were anti-imperialists, of course. Rather, I would argue they were Pakistani nationalists. Depending on the context, “Third World” nationalism can either collide with or align with imperial interests. In the case of the Afghan jihad (during which even China funded the insurgents) Pakistan’s perceived interests both converged with and diverged from those of the United States.

In the short term, Pakistan and the U.S. shared the immediate objective of ousting the Soviets. In the long term, however, disagreements over who should replace the PDPA government—Pakistan backing Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the U.S. favoring Ahmad Shah Massoud—played a significant role, alongside the nuclear issue, in the deterioration of U.S.–Pakistan relations in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s. Benazir’s rule was a partial exception, though tensions between Washington and Islamabad’s military-intelligence apparatus fluctuated (depending on her control over them) even during her tenure.

Ammar also states:

“Washington identified the military as its preferred strategic partner in the region, setting in motion the decimation of left-wing and progressive organizations in the first decade of the nascent state.”

The striking contradiction in this claim is that during the “first decade of the nascent state”, “democracy” (at least as imagined by much of the Pakistani left, wherein feudal elites qualify as “democratic” actors, and the absence of a military uniform is the primary indicator of “democracy”) was in place. It was not the military but the Governor General who wielded supreme authority during this period.

Ammar argues that Ayub Khan’s perceived tilt toward the West “explains why” the first wave of “mass struggles” against his rule was led by “left-wing” student groups and trade unions. To substantiate this claim, he cites an article—written by himself—about the role of students in overthrowing authoritarian regimes.

Below is an excerpt from that piece.

“Indeed, the crescendo of this organization [National Students Federation] arrived in 1968, when a student-led movement erupted against the Ayub dictatorship, disrupting his celebration of a ‘decade of development.’

Students inspired workers, farmers and professional classes to openly air their grievances against the junta, eventually forcing the US-backed military dictator to resign in the midst of a popular upheaval. It was these student agitators, reviled today in revisionist history, who paved the way for the first general elections in the country, thus becoming the forebears of democracy in the country.”

Absent, of course, is any serious reckoning with the chaos of early Pakistani politics—dominated by bickering feudal elites—and how their political maneuvering ushered in the first military coup. Equally absent is a concrete analysis of the common pattern of military interventions (not always due to U.S.-backed coups) within post-colonial political environments.

It is worth noting some aspects of Ayub Khan’s foreign policy that may allow us to formulate a more balanced perspective.

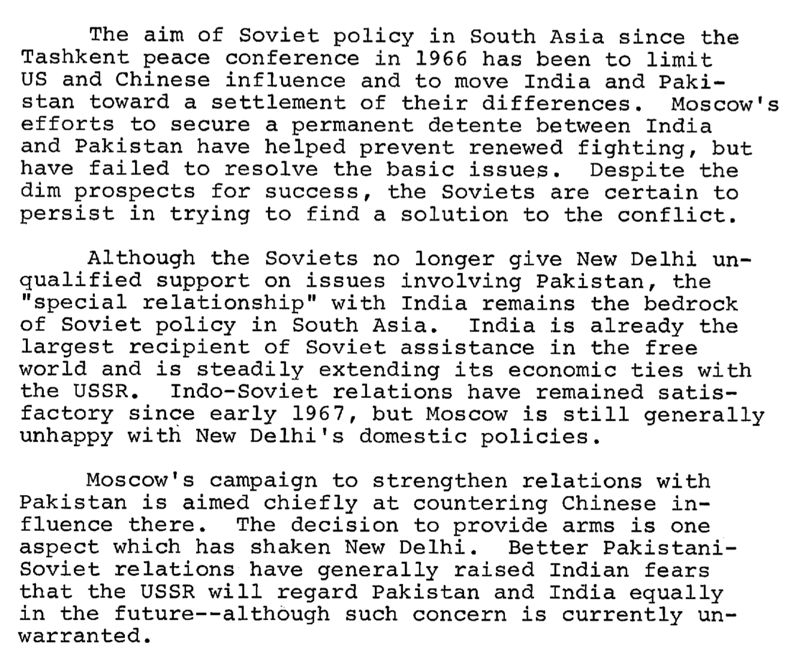

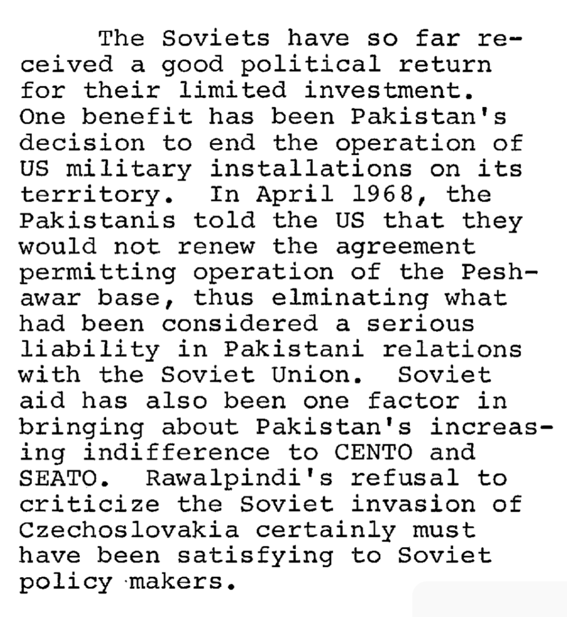

Ayub Khan secured military aid from the Soviet Union—a first in Pakistan’s history. At the time, Soviet policy towards South Asia was driven by concerns about U.S. influence in the region and Pakistan’s growing reliance on communist China. Following the 1966 Tashkent Conference, the USSR adopted a more measured stance on Kashmir, and in 1968, Ayub Khan informed the U.S. that Pakistan would not renew its commitment to the Peshawar base.

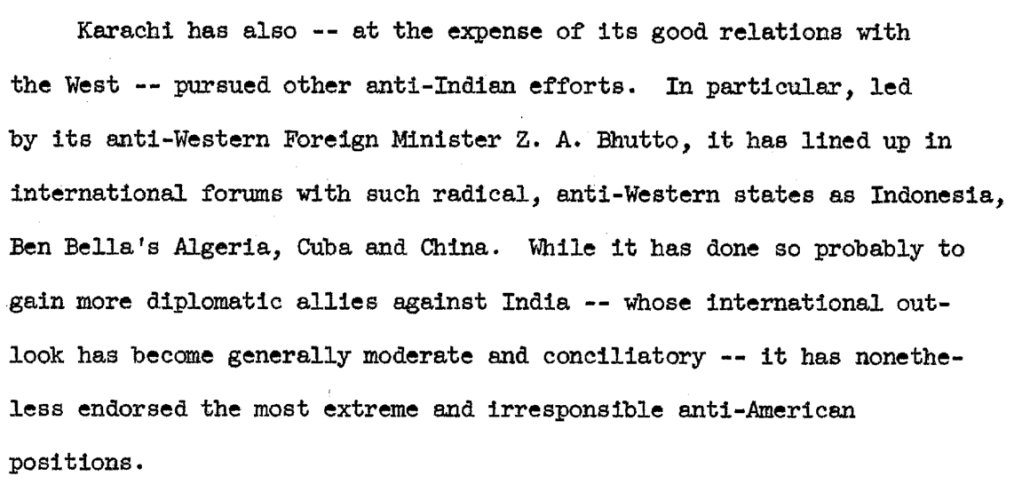

It was also Ayub Khan who appointed “revolutionary” Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as his Foreign Minister. In the wake of India demonstrating that its non-alignment policy by no means, translated into anti-imperialism, Bhutto courted Cuba, Algeria, Indonesia, and China in his diplomatic efforts against our hostile Eastern neighbor.

Following Ayub Khan’s resignation, General Yahya Khan imposed martial law and oversaw the 1970 general election to which Ammar refers.

In 1971, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was appointed Chief Martial Law Administrator (CMLA) by Yahya Khan. Through this route, he became President and, later, Prime Minister of Pakistan in 1973. It was only after Bangladesh emerged as an independent state that Bhutto “secured” a parliamentary majority and assumed the premiership—a far cry from the groundbreaking democratic triumph often portrayed by the left.

On that note, let us revisit Bhutto’s tenure, for it is often obscured by historical revisionism that whitewashes and glorifies a deeply corrupt, feudal leadership. A 1979 leaked U.S. Embassy cable provides a useful summary of what it describes as an “extraordinary and paradoxical leader”.

Regarded widely outside of Pakistan, and by many of his admiring countrymen, as a statesman of extraordinary ability, it was the same Bhutto who inspired the disastrous 1965 war with India over Kashmir, and who, more than any other political figure in then West Pakistan, made inevitable the1971 Bangladesh debacle.

In both instances, he skillfully evaded responsibility for the consequences and plucked personal victories from his country’s defeats.

In his dealings with the U.S., Bhutto was in the 60’s a demagogic critic in the style of his own heroes, Sukarno and Nkrumah. After assuming power in 1971, Bhutto anchored his foreign policy on a close relationship with the U.S. until internal pressures in the 1977 campaign to unseat him convinced him that the U.S. could be usefully flogged as a foreign devil seeking his overthrow.

Bhutto revolutionized Pakistani politics with his slogan of “freedom, clothing and shelter.” following limited efforts to institutionalize his revolution, Bhutto turned his back on his original constituency and forged a “traditional” Pakistani political alliance of landlords and bureaucrats -supported by a seemingly tamed military.

Bhutto’s constitution, adopted almost unanimously by supporters and opponents alike, was a model of rational federalism for this ethnically and linguistically divided country. but the ink was barely dry, when Bhutto systematically twisted its spirit and ultimately its letter destroy his enemies and to perpetuate his own rule. — ruthless in his politics, he was equally ruthless in personal relationships.

By 1977, few of his original close supporters remained with him and those who did had lapsed into sycophancy and suffered repeated humiliations. The eerie silence of his supporters in Bhutto’s final months of agony is testimony not only to the efficiency of the martial law regime but to an ambivalence toward their leader among the cadres Bhutto systematically abused when he held power. — and yet — he retains a hold on the masses that the endless catalogue of his crimes and errors can not obliterate.

For millions of Pakistanis, it was Bhutto alone who symbolized and personified leadership that cared for their welfare. His repeated betrayals of their interests was overwhelmed in the demagoguery, the spectacular showmanship, the performance on a world stage, which Bhutto gave a Pakistan starved for entertainment and leadership…History will undoubtedly treat him harshly, for the evil that he did will certainly live after him. but the Pakistani masses — whose voice is so rarely heard — will remember him as a man who seemed to care when no one else did.

If popularity is the metric by which we judge our past leaders, then surely we must consider that many Pashtuns—pleased with the level of autonomy provided to them by Ayub Khan (also a Pashtun), took to the streets in violent demonstrations of support for him during protests against his rule.

Under Ayub Khan, the former “North-West Frontier Province” (NWFP) received a disproportionate share of development funds, which is precisely the kind of corrective redistribution the Pakistani state should pursue (at least under a capitalist framework) to address the uneven development inherited from our colonial legacy; the current method, by contrast, relies predominantly on population-based formulas.

This period represented a rare—and, to date, unmatched—moment of stability (though class contradictions persisted—as they do now) in the province, where even the tribal areas were at least broadly (albeit, superficially) content with central authority.

Hilariously, even during Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s tenure—the rural areas of Pakistan retained significant support for Ayub Khan. A leaked U.S. Embassy cable from 1974 notes:

“I would guess that Bhutto has no fear of Ayub anymore that goes beyond mild irritation over such things as the fact that Ayub’s picture is still everywhere in the country. Also, there is little doubt that he is still held in high esteem throughout the countryside.

Were chaotic conditions to return to Pakistan there undoubtedly would still be posters and slogans calling for Ayub’s return, but it would seem that could hardly materialize as the majority managerial talent in this country would surely know that he just wasn’t up to it anymore.”

Had Ammar approached history with more rigor, he might better grasp why PMKP critiques the left’s support for the MRD and links it to its ongoing liberalization.

Interestingly, PMKP made similar historically inaccurate points—for example framing the Pakistani military’s relationship with China as a recent development and referencing a Kashmir independence movement in 1947 that did not exist.

Kashmir remains a profound and enduring failure of the Pakistani left.

Despite claiming to champion the principle of self-determination, many on the left have mocked the Pakistani state’s support (which they ought to investigate, particularly with respect to how it is perceived in Indian Occupied Kashmir) for the cause, drawn false parallels between Balochistan and Kashmir that collapse under minimal scrutiny, and even applauded the Musharraf-era attempt at de facto normalization of the Line of Control—an initiative rejected by both pro-independence groups (a movement that emerged long after 1947) and pro-Pakistan Kashmiris alike.

Nonetheless, PMKP’s recognition of the left’s failures on this front is welcome, as is its awareness of the tunnel vision of the unapologetically pro-India left. Their article raises many important points and offers a thorough, well-executed analysis of the Pakistani left’s past and present contradictions. While I disagree with its characterization of China as “social-imperialist,” this issue—along with other strategic questions raised by PMKP and others—will be examined in greater depth in Part 2 of this series.

Moving back to Ammar—he speaks of how the “left’s struggle” against the military won political and judicial rights for “our people.” But from a Leninist perspective—when the parliament is packed with feudal lords, the bureaucracy acts as a politicized elite, feudalism remains entrenched in Southern Punjab, Sindh, much of Balochistan, and parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and judicial rulings can be purchased—whose rights are we talking about?

Additionally, Ammar ignores that in addition to CIA-backed military coups (which we have not had) against democratically elected governments in post-colonial states—there have also been left-leaning or populist nationalist and socialist military coups that replaced corrupt “democratic” civilian leaders and monarchies.

Some of these include: Gamal Abdel Nasser (replaced the monarchy), Muammar Gaddafi (replaced the monarchy), Thomas Sankara (replaced a corrupt civilian government), Hafez al-Assad (replaced a corrupt civilian-military government), Juan Velasco Alvarado (replaced a corrupt civilian government), and Hugo Chavez (failed military-led coup to replace a corrupt civilian government, eventually came to power through an election).

Since 2020, we have witnessed a wave of left-leaning and Marxist-Leninist military coups across the Sahel—nearly all of which replaced corrupt or dynastic civilian regimes.

Ammar’s attempt to equate CIA-backed military coups with Pakistan’s martial-law periods rests on a superficial emphasis on uniforms rather than the political orientation or imperial alignment of the governments being removed. By this logic, one might forget that Muammar Gaddafi was ultimately killed by U.S.-backed Al Qaeda affiliates, or that Bashar al-Assad was targeted by the same forces.

Pakistan has not been fortunate enough to have its own Thomas Sankara or Ibrahim Traore, but we do have a “left-wing” that has historically recoiled even from periods of objectively superior military governance—Ayub Khan’s era being the clearest example (though I would welcome any evidence showing that the feudal political chaos preceding him was somehow better).

While I don’t argue that the left should have embraced Ayub’s rule, I do think it should have sought a genuinely revolutionary alternative to his protégé, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto—who, as a reminder, rose to power by appointment rather than election.

Rather than casting Ayub as a uniquely authoritarian figure, we ought to acknowledge that Bhutto was scarcely distinguishable on this front. To accept either leader, and to defend a nominal democracy functioning within an intrinsically anti-democratic structure, is to compromise the fundamental commitments of socialism.

Some will push back against these nuances because they unsettle the stories they’ve grown too comfortable with. Yet unless we interrogate our history from outside the standard script, and recognize the ways our judgments are shaped by factional loyalties and external influence, we deny ourselves the clarity needed to think beyond the narratives handed down to us.

On a final note, I urge Pakistani leftists to examine the graph below, which illustrates military sales or aid to Pakistan by country from 1947 to 2021.