For over four decades, Afghanistan has served as a geopolitical battleground, exploited by both regional and global powers to advance their strategic interests—from the Cold War to the so-called War on Terror.

In Pakistan, many have internalized a misleading narrative—popularized by Western think tanks—that there is “no good or bad Taliban.” This framing erases the long-documented distinctions between the Afghan and Pakistani Taliban (TTP), including the fact that fighters from the latter went on to form the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), the sworn enemy of the Afghan Taliban.

While neither group aligns with left-wing ideals, and their ties have grown closer in recent years, these differences still matter. What is rarely acknowledged is that the U.S.-led occupation itself relied on a distinction between “good and bad mujahideen”—a distinction rooted in the fragmented landscape of the anti-Soviet Afghan jihad and the civil wars that followed.

Without revisiting that period, the rise of the Afghan Taliban, the post-9/11 NATO occupation, and the eventual emergence of the TTP cannot be fully understood.

First Afghan Civil War (1979-1992)*

The table below summarizes the major mujahideen factions during the First Afghan Civil War (later rebranded as the “Soviet-Afghan War“).

While most of these groups received support from multiple foreign countries involved in the conflict, each external actor had its “favorites”—factions they prioritized in hopes of shaping the post-war outcome to best suit their interests.

This list is not exhaustive, as there were over one hundred mujahideen groups, but it covers the key players (who also acted as political parties, especially after 1989) relevant to understanding the Afghanistan’s post-1979 political landscape.

| Faction | Leader | Ideology | Preferred By | Northern Alliance | NATO Support Post-2001? | Notes |

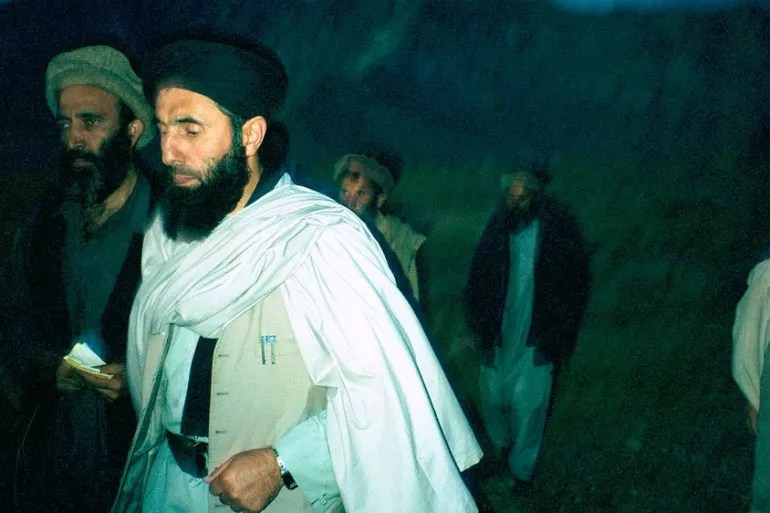

| Hezb-e Islami (Gulbuddin) | Gulbuddin Hekmatyar | Radical** Islamism, described as “Afghan Khomeini”, anti-West | Pakistan | No | No, but made peace in 2016. | Hekmatyar had originally been a pro-Soviet militant for the PDPA. His ideology eventually evolved into a more “Khomeinist” one. Pakistan saw him as ideologically safe and loyal, diverting most U.S. funded weapons to his faction. |

| Jamiat-e Islami | Burhanuddin Rabbani / Ahmad Shah Massoud | Moderate*** Islamism, pro-West, open to monarchial rule | U.S., U.K., France | Yes | Yes | Massoud and Rabbani were Western darlings. Massoud was killed two days before 9/11, but in the 90s he was in regular contact with the CIA, Jamiat-e-Islami was accused of massacres against Shia Hazaras in the 90s. |

| Hezb-e Islami (Khalis) | Yunus Khalis | Islamism, Pashtun traditionalism | Saudi Arabia | Yes | Played both sides. Suffered various splits, including one that led to the formation of the Tora Bora Military Front in 2006. | Formed after a split between Hekmatyar and Khalis took place in 1975. Several current Taliban leaders, including the Supreme Leader, hail from HIK. Had good relations with Jamiat-e-Islami. Some of its top commanders, such as Abdul Haq, were said to be “favorable towards the West”. |

| Hezb-e Wahdat (formed 1989 from Tehran Eight, had multiple splits in later years) | Abdul Ali Mazari (later) | Islamism + Hazara nationalism | Iran | Initially, yes, switched sides by 1993, then switched again, ultimately broke into several factions. | After a split, some supported the Taliban or made tactical alliances with other groups against NATO. Others supported NATO. | Aligned with Iran’s goal of countering Saudi influence and uniting the Shias of Afghanistan. Formed a tactical alliance with Hekmatyar in 1993 against Massoud, Rabbani, and Sayyaf.. Known for being inclusive, had 10 women in its central council. |

| NIFA (National Islamic Front of Afghanistan) | Pir Ahmad Gailani | Sufism, Royalism, close to former monarchy | U.S., U.K. | Yes | Part of Bonn Conference and supported the NATO-backed regime but had little military role. | NIFA appealed to Western nostalgia for the Afghan monarchy. Seen as a “gentleman’s faction”, diplomatically presentable but militarily weak. |

| Afghan National Liberation Front (ANLF / Jabha-e Nejat-e Milli) | Sibghatullah Mojaddedi | Islamism, Sufism Royalism, fiercely anti-communist, open to secular republic under the former monarchy | U.S., U.K. | Yes | Yes | Mojadeddi was the first to call for jihad against the PDPA government. The U.S. liked his support for “democratic governance”. He tried to assassinate Nikita Khruschev I (who was on a visit to Kabul) in 1959. |

| Ittehad-e Islami | Abdul Rasul Sayyaf | Wahhabi/Salafi-inspired Islamism, anti-Shia | Saudi Arabia | Yes | Yes | Sayyaf was a direct conduit for Saudi Wahhabism and brought bin Laden to Afghanistan. Accused of massacres against Shia Hazaras in the 90s. The terrorist group and ISIS affiliate “Abu Sayyaf” is named after him. He has also sent jihadis to Chechnya. However, this did not stop him from being a key NATO ally post-2001, including serving in parliament. He has been living in India since the Taliban takeover in 2021. |

| Harakat-i-Inqilab-i-Islami | Mohammad Nabi Mohammadi | Pashtun traditionalism, clerical, pro-monarchy | Unclear | No | No, inactive by 2001. | Like Pir Ahmad Gailani, Nabi Mohammadi was a cleric who preferred the return of Afghanistan’s traditional elites to power. |

*For the First Afghan Civil War, this article focuses on the 1989-1992 period as it is most relevant to how divisions amongst the mujahideen and their foreign backers contributed to the continued conflict in Afghanistan, and eventually, the rise of the Taliban. This period of the war is also frequently misunderstood and has been the subject of a great deal of historical revisionism from the West.

**The term “radical Islamism” (when used by the West) has historically meant an individual or group was not just an Islamic fundamentalist, but also anti-West. Interestingly, a 1980 declassified CIA file reveals Hekmatyar was the “more secular” of the mujahideen leaders, and his opposition to restoring the Afghan monarchy isolated him from other groups.

***The term “moderate Islamism” (when used by the West) has historically meant Islamic fundamentalism that is not hostile to the West. As noted in the table, the groups described as moderates by the West were often the most sectarian.

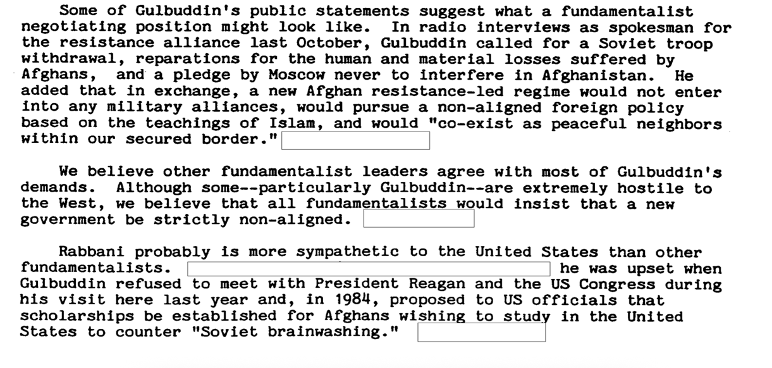

Ahmad Massoud and Burhanuddin Rabbani were favored by Western powers due to their lack of hostility to them—especially in contrast to Hekmatyar. A declassified CIA file from 1986 reveals that the U.S. was concerned about the latter’s views even when he was technically their ally.

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, internal fighting among the mujahideen escalated significantly. The most intense and long-standing rivalry was that of Ahmad Massoud—leader of the Jamiat-e Islami and the Shura-e-Nazar coalition—against Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e Islami.

In the years following 9/11, Western media has occasionally portrayed Gulbuddin Hekmatyar as a former “CIA favorite,” largely due to his prominent role in the first civil war.

But such narratives oversimplify a more nuanced reality: Hekmatyar was never genuinely favored by the United States, primarily due to his anti-Western views and strong opposition to the Afghan monarchy.

During the Soviet presence, the U.S. funneled weapons and resources to the mujahideen exclusively through Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), which blocked the CIA from having direct contact with the insurgents. The ISI, in turn, prioritized Hekmatyar—its favored leader.

His staunch anti-monarchy stance made him particularly useful to Islamabad, which remained wary of former King Zahir Shah’s support for Pashtun and Baloch separatist movements inside Pakistan.

By contrast, most other mujahideen factions were either openly pro-monarchy, aligned with Western interests, or vague about their vision for post-communist Afghanistan.

It was this underlying distrust that shaped U.S. policy after the Soviet withdrawal. Rather than supporting Hekmatyar in the ensuing political order, American efforts shifted toward backing rival factions to diminish his influence—a decision that played a significant role in fueling the second civil war that erupted in 1992.

The CIA’s failure to secure direct access to the insurgents earlier was criticized by Western media after the Soviet withdrawal, as well as by U.S. Congress years after the fact.

In 1989, the CIA, who had halted aid to the ISI the same year, became more directly involved with fighters on the ground, favoring Massoud and Rabbani’s Jamiat-e-Islami. Pakistan subsequently began arming Hekmatyar on its own.

Referring to the 1989 Battle of Jalalabad, journalist and historian, Steve Coll writes:

“In 1990 the CIA’s secret relationship with Massoud soured because of a dispute over a $500,000 payment. Gary Schroen, a CIA officer then working from Islamabad, Pakistan, had delivered the cash to Massoud’s brother in exchange for assurances that Massoud would attack Afghan communist forces along a key artery, the Salang Highway.

But Massoud’s forces never moved, so far as the CIA could tell. Schroen and other officers believed they had been ripped off for half a million dollars.”

Human Rights Watch’s Afghanistan researcher, John Sifton, reported that covert CIA support to Massoud continued through the late 1990s.

“The CIA has a long history of using cash to buy allegiance in Afghanistan. A retired CIA officer once told me unabashedly over lunch at the Cosmos Club in Washington of payments in the late 1990s to the anti-Taliban leader Ahmed Shah Massoud.”

The Battle of Jalalabad was a disaster for the mujahideen, destroying much of the city and failing to achieve its intended goals of installing a mujahideen-led government. Naturally, the U.S. subsequently distanced itself from the debacle.

In 2015, Abbas Nasir, former editor of NATO-aligned media outlet Dawn, claimed:

“After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, as the director-general of the Pakistan’s intelligence organisation, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) directorate, an impatient Gul wanted to establish a government of the so-called Mujahideen on Afghan soil.

He then ordered an assault using non-state actors on Jalalabad, the first major urban centre across the Khyber Pass from Pakistan, with the aim capturing it and declaring it as the seat of the new administration.“

Following the First Afghan Civil War, the narrative that Pakistan sought to ‘conquer’ Afghanistan through its proxies—as echoed in Nasir’s account—gained traction in Western-aligned media, think tanks, and revisionist history books.

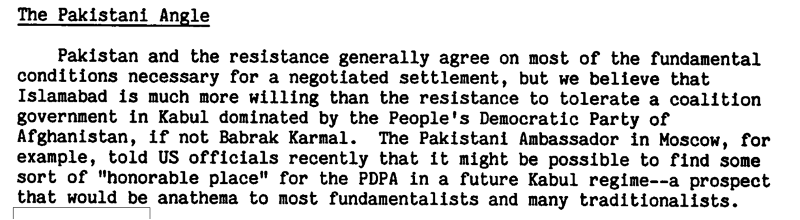

However, a CIA brief from 1986 suggests a different picture: that Pakistan was open to a settlement involving a PDPA-dominated coalition government.

Another declassified document from 1985 further illustrates Pakistan’s calculated approach. As the CIA was preparing a mujahideen delegation to appear before the UN General Assembly, it was Pakistan—not the U.S.—that expressed reservations. Islamabad was concerned that such a public appearance could complicate the ongoing Geneva negotiations and damage its image, particularly at a time when the U.S. had kept its own role in the conflict low-profile.

Additional corroboration of the Americans’ push for the Battle of Jalalabad is found in a 1989 PBS interview where journalists, professors, and State Department officials admit that more than anyone, it was the U.S. who was intent on a military solution.

One of the interviewees, Professor Halliday, noted:

“The Americans have not altered their policy. They are still going for a military solution in Afghanistan. They are saying that it is going to take longer.

It might take two or three years but they are going to put more weapons into Afghanistan, they are still encouraging the Pakistanis to go in to Afghanistan and support the guerillas. So therefore the Americans have retreated from their most optimistic strategy but have come up with a new one. They are talking about stamina, the long haul, a war of attrition.”

While the failed assault marked a major temporary setback for the mujahideen, the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union critically weakened the PDPA government, culminating in its collapse the following year and triggering a descent into anarchy and renewed civil war in Afghanistan.

Second Afghan Civil War (1992-1996)

After the fall of President Najibullah’s government in 1992, most of the mujahideen factions that would later form the Northern Alliance signed the Peshawar Accords, establishing Ahmad Shah Massoud as defense minister and Burhanuddin Rabbani as president (after Sibghatullah Mojaddedi’s brief stint) of the Islamic State of Afghanistan.

The Islamic State enacted various oppressive laws against women, however, these were later whitewashed by the U.S. to justify the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan.

According to an article published by The New Yorker, they:

“Issued a decree declaring that “women are not to leave their homes at all, unless absolutely necessary, in which case they are to cover themselves completely.” Women were likewise banned from “walking gracefully or with pride.” Religious police began roaming the city’s streets, arresting women and burning audio- and videocassettes on pyres.“

In a 2001 UK Parliament debate, officials reflecting on their renewed alliance with Rabbani’s government acknowledged that, like the Taliban—whom NATO claimed to be fighting to protect women from—his administration also enforced strict dress codes such as the hijab and chador.

The Islamic State under Rabbani imposed gender segregation and demanded the dismissal of women from jobs in UN agencies and NGOs. Officials also noted that even in 2001, at the start of the Bonn Talks, many of the same former leaders of the Islamic State of Afghanistan banned a peaceful rally for women’s rights.

Though he was offered the role of prime-minister under the Peshawar Accords, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, backed by Pakistan’s military-intelligence apparatus, rejected the agreement, as did the vast majority of mujahideen groups. He viewed Massoud and Rabbani as subservient to foreign interests that would compromise his “Khomeinist” vision for post-war Afghanistan, which was increasingly alarming for Western policy circles.

Since the Islamic State was the UN-recognized government of Afghanistan, neither Pakistan nor Hekmatyar openly defied it at first, though fighting had already broken out among the mujahideen.

In 1993, Hekmatyar, who had “accepted” the position of prime minister to appear cooperative, dismissed the government, claiming there was “no need for it anymore“. He had been collaborating with Pashtuns from the Khalq faction of the former PDPA forces, quietly building military capabilities just outside Kabul in preparation to capture the city.

The external actors of the previous conflict continued arming their preferred mujahideen against their rivals during this period,

An article from the Washington Report for Middle East Affairs notes:

“By the time mujahedeen forces reached Kabul in April 1992, the various factions supported by Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United States and Russia, each with their own regional agenda, were armed to the teeth.“

India also established its presence in Afghanistan, arming and training Massoud’s fighters. This fact is frequently ignored in mainstream discourse today, which tends to disproportionally blame Pakistan and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar for the conflict.

According to an article published by the Middle East Institute, which criticizes Pakistan for refusing to accept Massoud and Rabbani, the Pakistani military defended its decision on the basis of securing “strategic depth” and regional unity amongst predominantly Muslim countries.

“General Beg defends the idea and argues that the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan, Iran’s emergence as a strong player after its war with Iraq, and the end of Zia ul-Haq’s dictatorship in Pakistan had prepared the ground for the unity of these three Muslim countries “as the bastion of power, to defeat and deter the common enemies … [and] achieve the essential element of ‘Strategic Depth.’” He blames the “enemies” for causing the civil war in Afghanistan to “defame and defeat” the unity initiative.”

By 1993, the Iran-backed Shia Hazaras of Hezb-e-Wahdat, who initially supported the new government, formed a tactical alliance with Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e-Islami.

Though they were initially given minor roles in the Islamic State government, they were increasingly sidelined and discriminated against due to their ethnicity and religion.

Some former senior army officers such as Abdul Rashid Dostum, flip-flopped sides frequently. He was known for switching over to the “winning side” at key turning points, as he had done so just a few years prior when he defected from the communist government.

Initially supporting Rabbani and Massoud, Dostum switched to Hekmatyar’s side by 1994. In 1996, he changed sides again, backing Rabbani and Massoud, this time firmly placing himself within the Northern Alliance, whom he fought alongside after 2001, as well.

Frequently shifting alliances have been a defining trend of conflicts in Afghanistan.

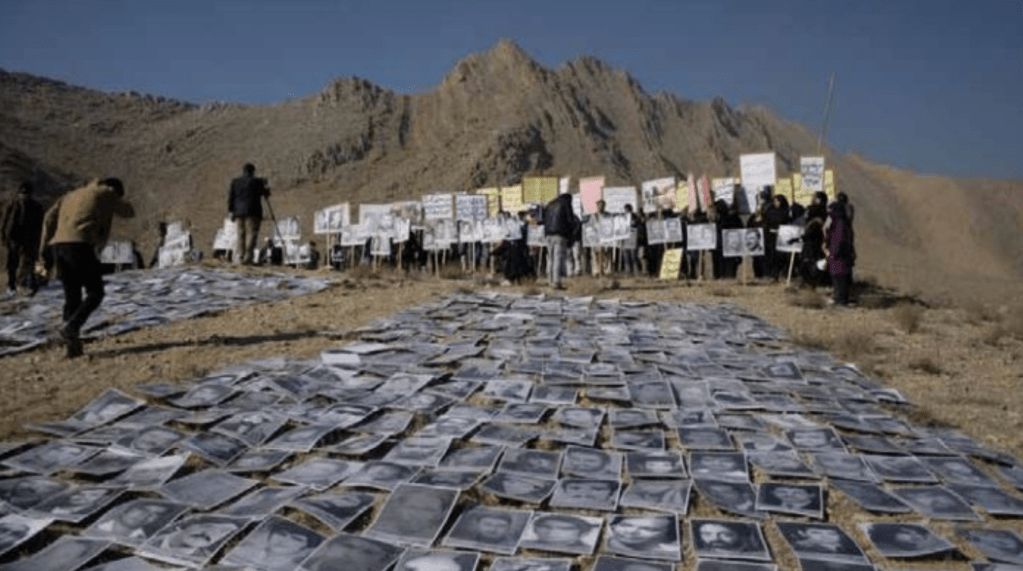

At least 500,000 residents of Kabul—where much of the heavy fighting was concentrated—fled the city.

Though all sides committed atrocities, Massoud, Rabbani, and Sayyaf (aligned with the government) were accused of the most egregious, particularly due to their forces’ sectarian attacks against Shia Hazaras and habitual molestation of male children.

Referring to Ittehad’s (led by Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, part of the Northern Alliance) war crimes, a resident told Reuters:

“The guerrillas were going from house to house, saying they wanted to kill all the Shi’as.”

Sectarian violence against Shia Hazaras became a common pattern for the Islamic State government-aligned forces.

According to Human Rights Watch:

“In March 1995, Massoud forces were responsible for rape and looting after they seized control of Kabul’s predominantly Hazara neighborhood of Karte Seh.

On the night of Feb. 11, 1993, the Massoud and Sayyaf forces conducted a raid in west Kabul, killing Hazara civilians and committing widespread rape. Estimates of fatalities range from 70 to more than 100.“

In 2001, a BBC reporter noted the lingering impact of the government-aligned forces’ atrocities during the 1993 Afshar Massacre, when Hezb-e-Wahdat clashed with Saudi, United States, and India-backed Sunni militants, marking what would become the first known major sectarian massacre in Afghanistan’s history.

“It was the site of repeated human butchery during fighting between a faction that adheres to the Shi’ite Muslim faith and followers of a Saudi backed Mujahideen leader, Abdul Rasul Sayyaf.

Amnesty International reported that Sayyaf’s forces rampaged through Afshar, murdering, raping and burning homes.”

In a video recorded during the height of the daily massacres, members of the Hazara community recount the atrocities committed by Massoud, Sayyaf, and their allies. Witnesses describe individuals being beheaded solely for being Shia.

One woman recalls armed men storming homes while reciting the azan (call to prayer), forcing wives to watch as their husbands were slaughtered before their eyes.

One will rarely find these atrocities documented in Western media or academic “research” without an immediate attempt to draw moral equivalence by accusing the Afghan Taliban of similar acts—often in the same breath.

This framing attempts to downplay the fact that the U.S. was openly aligned with these warlords, including Abdul Sayyaf, one of the principal perpetrators of the sectarian atrocities, before and after 9/11.

Sayyaf held prominent positions in the NATO-backed Karzai government. He helped ensure amnesty for war crimes committed by warlords, was opposed to women’s education, and now lives in exile in India—where he fled following the Afghan Taliban’s return to power.

Ahmad Massoud also looted Afghanistan’s emeralds for over a decade, shipping them off to the “affluent world”, which may explain why he continued to be a favorite of the West.

Criticism of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s role in the Afghan civil war has largely centered on his relentless rocket attacks on Kabul. However, forces aligned with the government were equally responsible for indiscriminate shelling of the city during the same period.

On one occasion, Rabbani bombed an entire hospital where Hekmatyar was getting treatment. As Hekmatyar’s Hezb-e-Islami was predominantly Pashtun, indiscriminate violence against the ethnic group had become increasingly common as well.

While Hekmatyar’s forces were not linked to violence against religious minorities, it’s crucial to note that no mujahideen faction spared women from their brutality during the war, according to reports compiled by RAWA. Widespread sexual violence by mujahideen commanders and their forces terrorized communities, driving many women to take their own lives to escape the threat of rape.

RAWA notes a particularly tragic case where a father, witnessing fighters approaching his home, shot his own daughter to “protect her from being raped”.

Incidents involving the “over enthusiasm” of Hekmatyar’s forces, such as recklessly shooting into the air and causing civilian casualties, were also reported. Additionally, as the civil war raged on, ethnic divisions between the warring factions grew increasingly violent, often dragging civilians into the bloodshed based solely on their ethnicity.

Though all sides were guilty, a disproportionate blame for the civil war has been placed on Gulbuddin Hekmatyar. Further, Hekmatyar is portrayed as the most extremist of the mujahideen, which, as demonstrated by declassified CIA files reviewed earlier, is a blatant lie. In the context of Afghanistan, a significant portion of the last 40 or so years of history have been rewritten. A great degree of this historical revisionism serves to obfuscate the role of the United States in engineering decades of chaos in the country, and as such, revisiting these stories from a truly anti-imperialist perspective is imperative.